Share:

As mentioned in this article, the squat is a foundational exercise to strength training and physical therapy programs.

There are many variations to the squat, and it can be overwhelming to try to decide what variation is right for you.

When deciding on a squat variation, you should always begin with your end goal or reason for performing the squat. Some example goals may be to build muscle mass (hypertrophy), strength, muscular endurance, stability, power, reduce pain, or because my PT told me I should.

Many people exercise because they want to feel and perform better. Squats are a compound (multi-joint) movement that is one of the most effective exercises for helping you do just that. Squats are also intimidating for many athletes, and they fear injury from them.

Athletes fear injury from squats because of personal experience or stories of others who have experienced pain during and/or after performing them. So, they have good reason for fearing them, right? Kind of, but there is often a variation or modification they can perform relatively pain-free and safely. Also, many have pain due to compensations, which I addressed in my previous blog.

In this article, I will cover the differences between the most common squat variations with an emphasis on how different squat variations affect joint stresses and require different levels of stability. This will give you confidence to continue squatting without fear of injury or in the case of pain/injury, to modify for success.

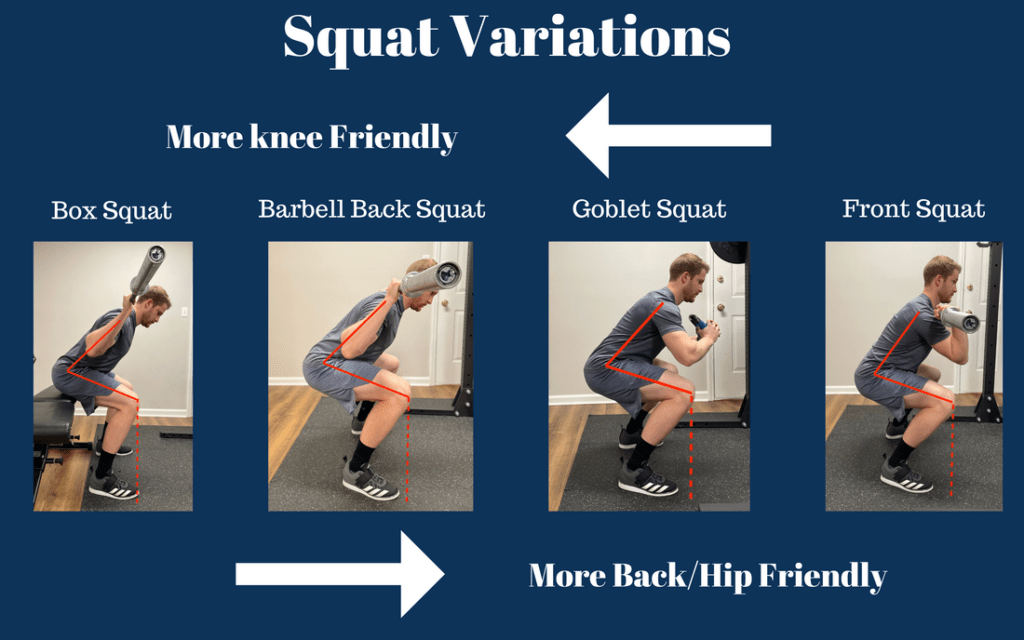

In the sections below, I give detail to the reasoning behind the this infographic. This infographic is a generalization and simplification for the layperson’s general benefit. For any astute biomechanics wizards out there, I understand that the science of calculating actual joint stresses during these variations is more nuanced and complex than this infographic.

“Knee Friendly” Squat Variations

The Barbell Back Squat

The back squat tends to facilitate a more forward trunk lean with hips driven backwards further. This places more strain on the low back and hips. At the same time, there tends to be less forward translation of the shin (anterior tibial translation). The more the shin translates forward, the more shear force at the knee. This is how the “no knees over toes” phrase became popularized.

The “knees over toes” during the squat debate is controversial in the fitness and physical therapy world. I tend to take a stance in the middle of the extremes on this debate.

You cannot deny that more stress is placed on the knee with the knees translating over the toes. Inherently, this can lead to knee pain. What has failed to be demonstrated with research (and my clinical experience) is that allowing your knees to translate over your leads to higher rates of pain/injury. This does not give you free rein to purposely try to drive you knees over your toes with heavy weight and reckless abandon….yes, I see you “knees over toes” guy.

If you are currently in knee pain, then modifying the squat variation to a more knee friendly variation may be needed in the short-term, The body is incredible at adapting. If you dose your training appropriately, then even heavy squats with allowing knees over your toes is likely safe. While I do not seem the harm in deep squats for many, unless you are a powerlifter or olympic weightlifter, then deep squatting is likely not necessary to accomplish your fitness goals. So, don’t sweat it if it is not your thing.

When someone is experiencing back or hip pain with squats with the absence of knee pain, I will often cue them to allow the knees to translate over their toes further to allow for the torso to stay more upright (less back/hip stress) as the descend into the squat. This is an example of how knowing the general joint stresses during squat variations can help you choose the right variation for your situation.

For weightlifting athletes that enjoy squatting, the back squat is by far the most common. This is because it is much easier to add heavier load (weight) with the back squat. Heavier resistance means a larger muscle force required to accomplish he lift, leading to larger strength and hypertrophy gains. Heavier resistance inherently places more stress on your joints, so progress slowly and listen to your body if you start to experience pain.

The Box Squat

The box (or chair) squat is more of a sub-variation than its own distinct variation. What I mean is it can be performed with a barbell in a back squat fashion, any version of front rack (front squat variations), or goblet squat.

The box often limits the depth (depending on the size of the box). The deeper you descend into the squat, the higher the stress placed on the knees; therefore, it is more knee friendly. The box also slows the movement down. Many people have a quick transition out of the bottom of the squat (“the hole”). Slower speeds reduce the rate of the load going through the body, further reducing the stress to the joints.

If you perform them with slower speeds and reduced depth, the box squat becomes back, hip, and knee friendly. It is one of my favorites to start people with when recovering from injury!

Back and Hip Friendly Squat Variations

KeepGoblet and front squats both have the resistance in front of your body (“front rack”) compared to back squats that have weight behind the body. This facilitates a more upright torso. The upright torso typically places less stress on your back and hips, but more on the knees. These squat variations are a good way to start squatting when recovering from back pain or if you have a history of back pain.

Front squats are easier to load heavy than goblet squats, which is a key factor when deciding the goal of your squat.

The Foam Roller/Physioball Squat aka “The Safest Squat

This squat is a variation of the wall squat. The purpose of the foam roller or physioball is to facilitate a smooth slide up and down during the movement.

Why is this squat “the safest squat?” As you can see, the torso and shin angle are nearly vertical during this squat, greatly reducing shear force to the back, hip, and knee joints. This squat is knee, hip, and back friendly. Add an isometric hold at the bottom to feel the burn on the quads!

Single Leg and Split Pelvis Squats

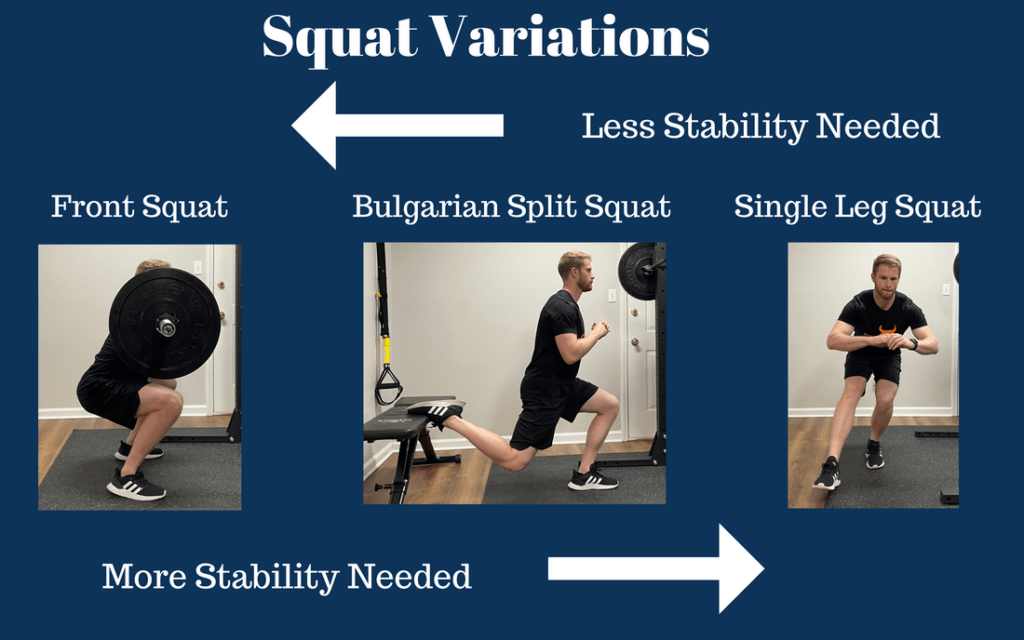

So far, I have only covered bilateral squat variations. The two other main squat variations are split pelvis (ie: Bulgarian split squats) and single leg squats (ie: pistol squats).

As you can see in the infographic, bilateral movements require the least amount of stability and single leg requires the most. The larger the base of support the less stability (balance) required.

When I talk stability, I am not talking about structural integrity of the body. I am talking about the neuromuscular system’s ability to coordinate a movement in a skilled fashion. This is a complex process that is influenced by a myriad of factors, and for the purposes of this blog, we are not going to go deep here today.

Split pelvis and single leg squats are often better for building stability while bilateral squat variations are better (for most people) for building strength and hypertrophy. This statement is also a generalization and simplification but tends to be true for many.

For example, if I want quads like Arnold, it would probably be hard to do that with only single leg (or even split pelvis) movements because stability will eventually be the limiting factor instead of muscle fatigue. I should clarify that I am talking about free-weight movements. If you are using leg press or leg extension machines, it is easy to reach a strength and hypertrophy stimulus because machines eliminate the need for stability by providing it for you.

If you are swaying all over the place like a bad dance move, then the stability challenge is too high, especially if strength instead of stability is the goal of the exercise.

Besides a stability challenge, single leg and split pelvis squats allow for a lower load to be added before fatigue is achieved. A lower load is advantageous when currently experiencing pain (less load means less stress on the body) or programming thoughtfully to manage overall load to the body.

In my clinical and fitness opinion, a well-rounded program that produces rock solid strength and stability will include bilateral, split pelvis, and unilateral squat variations

Conclusion

Squats are a crucial component to many physical therapy and fitness programs. If you are in pain or recovering from injury, knowing how different squat variations affect joint stresses and the different stability requirements needed can clarify which variation is right for your situation.

If you currently in pain or still unsure of how to squat safely, schedule an appointment with our expert team today!

Which squat variation/variations do you think are best for your goals and current health situation?

Blog by: Dr. Dylan Michel, PT, DPT

Disclaimer: Articles in the blog are not designed to be medical advice. If you have pain or an injury, I recommend seeing a healthcare professional. To schedule an appointment with Bull City Physical Therapy, visit our clinic page.

References

- Schoenfeld BJ. Squatting kinematics and kinetics and their application to exercise performance. J Strength Cond Res. 2010 Dec;24(12):3497-506. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181bac2d7. PMID: 20182386.

Get in touch with us

* indicates required fields